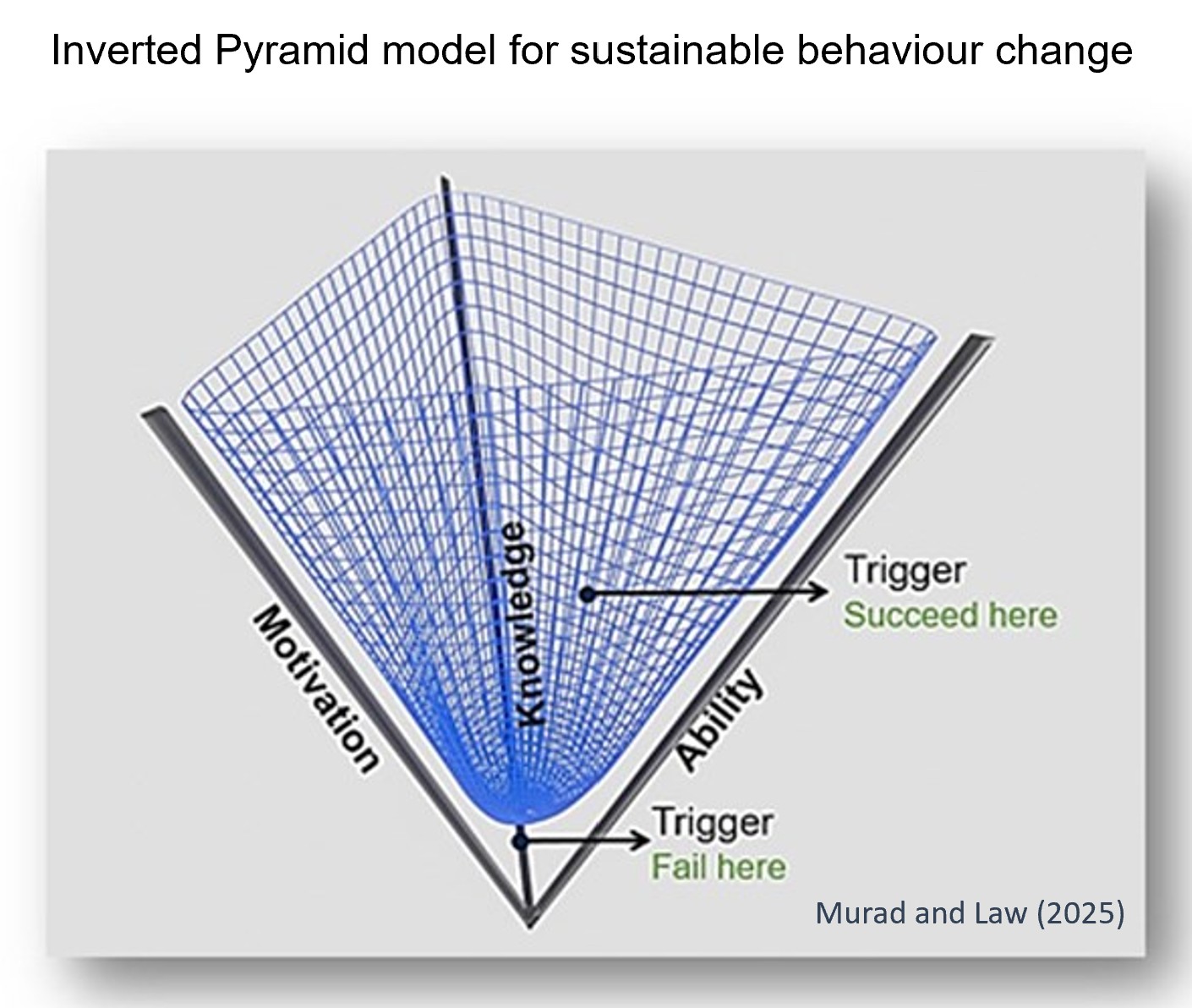

Inverted Pyramid Model for Sustainable Behaviour Change

An in-depth analysis of why this model is superior for creating lasting change

The Framework

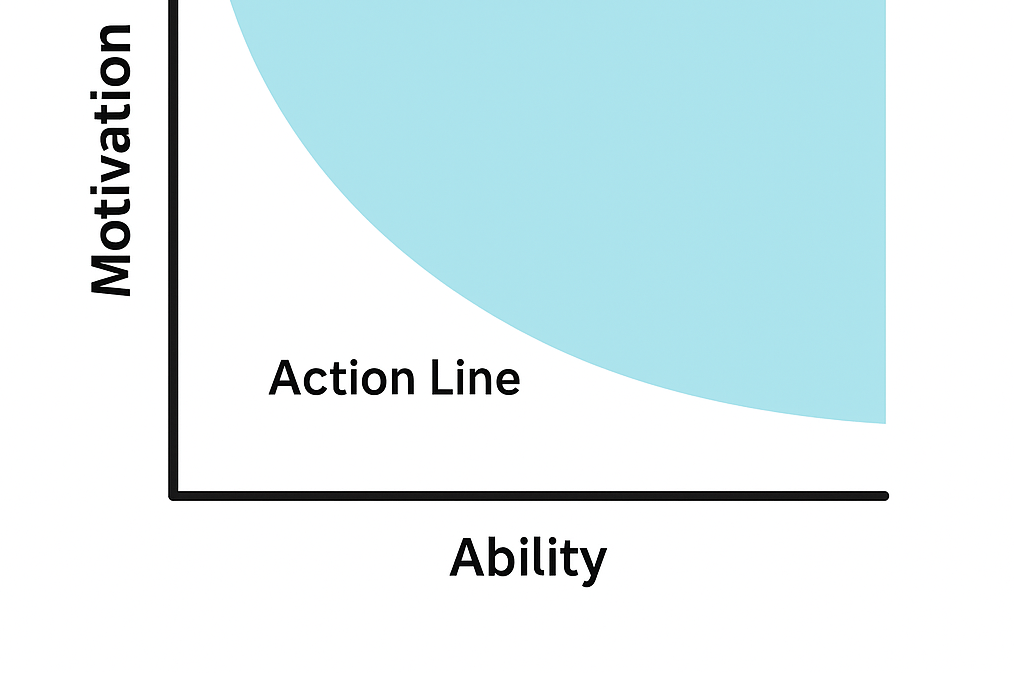

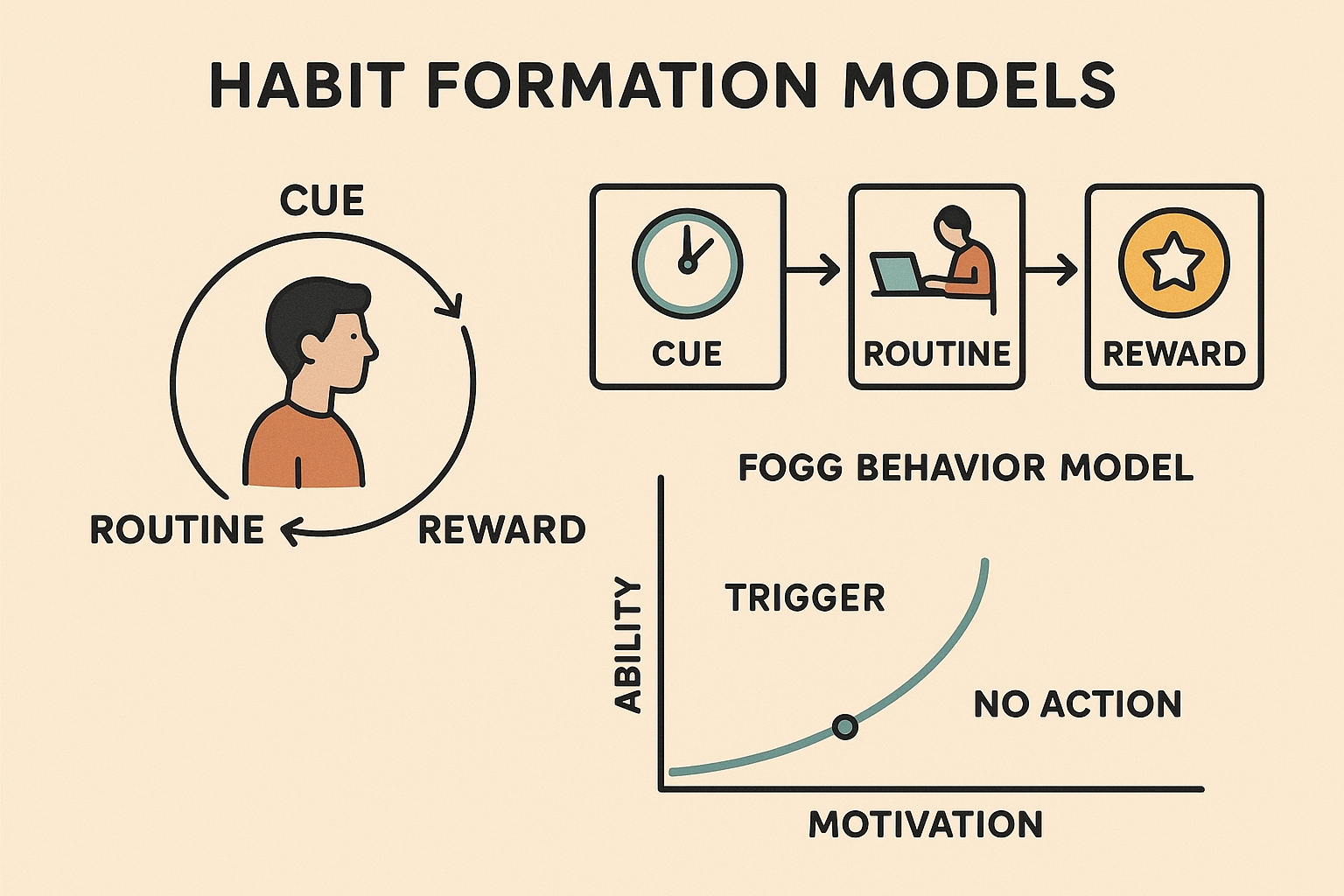

The Inverted Pyramid Model for Sustainable Behaviour Change suggests a trade-off relationship between motivation, ability, and knowledge, where all three must be at a non-zero level. In cases of very low motivation, ability, and knowledge, it is essential to focus on boosting these factors before implementing triggers. If triggers were used when these foundational elements were extremely low, they would likely fail; however, the same triggers may not reach their full potential when individuals have only achieved a minimum level of motivation, ability, and knowledge.

Minimum motivation can be measured by whether individuals find the proposed change interesting; for ability, the new target behaviour should not be drastically different from current practices; and they should have knowledge about their consumption and the potential impact of the new behaviour. Individuals may also have misconceptions about their abilities in the realm of sustainable behaviour change, which should be considered, and in some cases, providing realistic information can be beneficial.

The framework consists of four key elements:

- Knowledge and Awareness: Establishing a foundation of understanding about sustainability issues, such as the impact of carbon emissions and the importance of eco-friendly practices.

- Attitudes and Motivation: Encouraging positive attitudes and leveraging social norms to inspire a commitment to sustainable practices.

- Ability: To perform a target behaviour, a person needs the ability to do so. Supporting individuals (so it is easier to do) in adopting tangible sustainable behaviors, such as using public transport, reducing waste, or conserving energy.

- Triggers: External factors or cues that initiate sustainable behaviours when knowledge, ability, and motivation are adequately developed.

The Four Layers of Sustainable Change

Triggers

Activating behavior once the foundation is solid

Motivation

Leveraging intrinsic and identity-based drivers

Ability

Equipping individuals with skills and confidence

Knowledge

Understanding what and why change is needed

Why the Inverted Pyramid Model for Sustainable Behaviour Change Model is Superior

The Inverted Pyramid Model for Sustainable Behaviour Change Model tackles the core issue in many behavior change strategies: emphasizing immediate action over establishing a sustainable foundation. Unlike other models that concentrate on triggers, incentives, or prompts for rapid outcomes, they often fall short in fostering enduring change due to the absence of an adequate support structure.

Durable & Resilient

Resistant to relapse when external incentives disappear

Context-Sensitive

Knowledge is a key component, making it adaptable to different environments and situations.

Self-Sustaining

Fueled by knowledge and intrinsic motivation, rather than external pressure.

Scalable

Effective at both the individual and population levels

This foundational approach fosters lasting change even after external supports are withdrawn, proving uniquely effective for sustainable transformation across health, environmental, and social sectors.

Comparison with Other Models

| Feature | Inverted Pyramid Model | Traditional Models |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation First | ✓ Builds knowledge and ability before triggers | ✗ Often starts with prompts or incentives |

| Sustainability | ✓ Long-lasting change | ✗ Short-term results often fade |

| Adaptability | ✓ Context-sensitive application | ✗ One-size-fits-all approach |

| Reliance on External Factors | ✓ Minimal, focuses on intrinsic motivation | ✗ Often requires continuous external triggers |